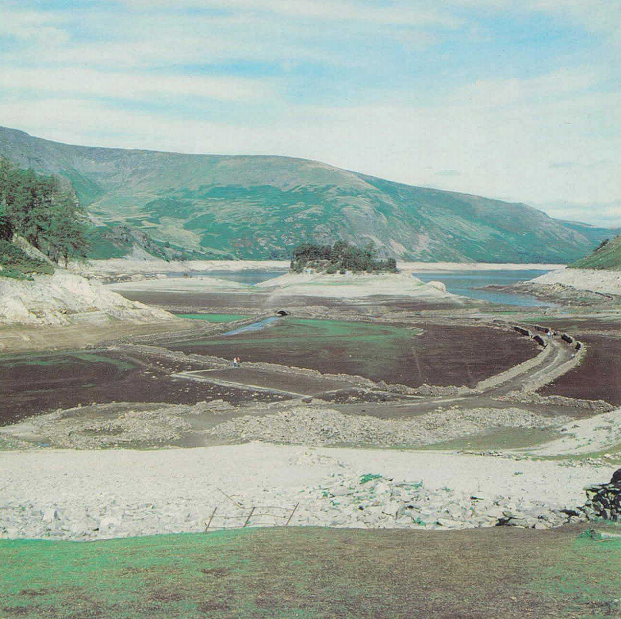

River flows and reservoir stocks declined steeply through the spring and Drought Orders were widespread by mid-summer. Heavily depleted reservoir stocks, for instance in north Wales and the Lake District, threatened the water resources outlook for some conurbations (e.g. Liverpool) dependent on regional water transfers. Fortunately, the UK’s second wettest autumn in the last 32 years brought a rapid termination to the drought conditions in almost all of the impacted areas.