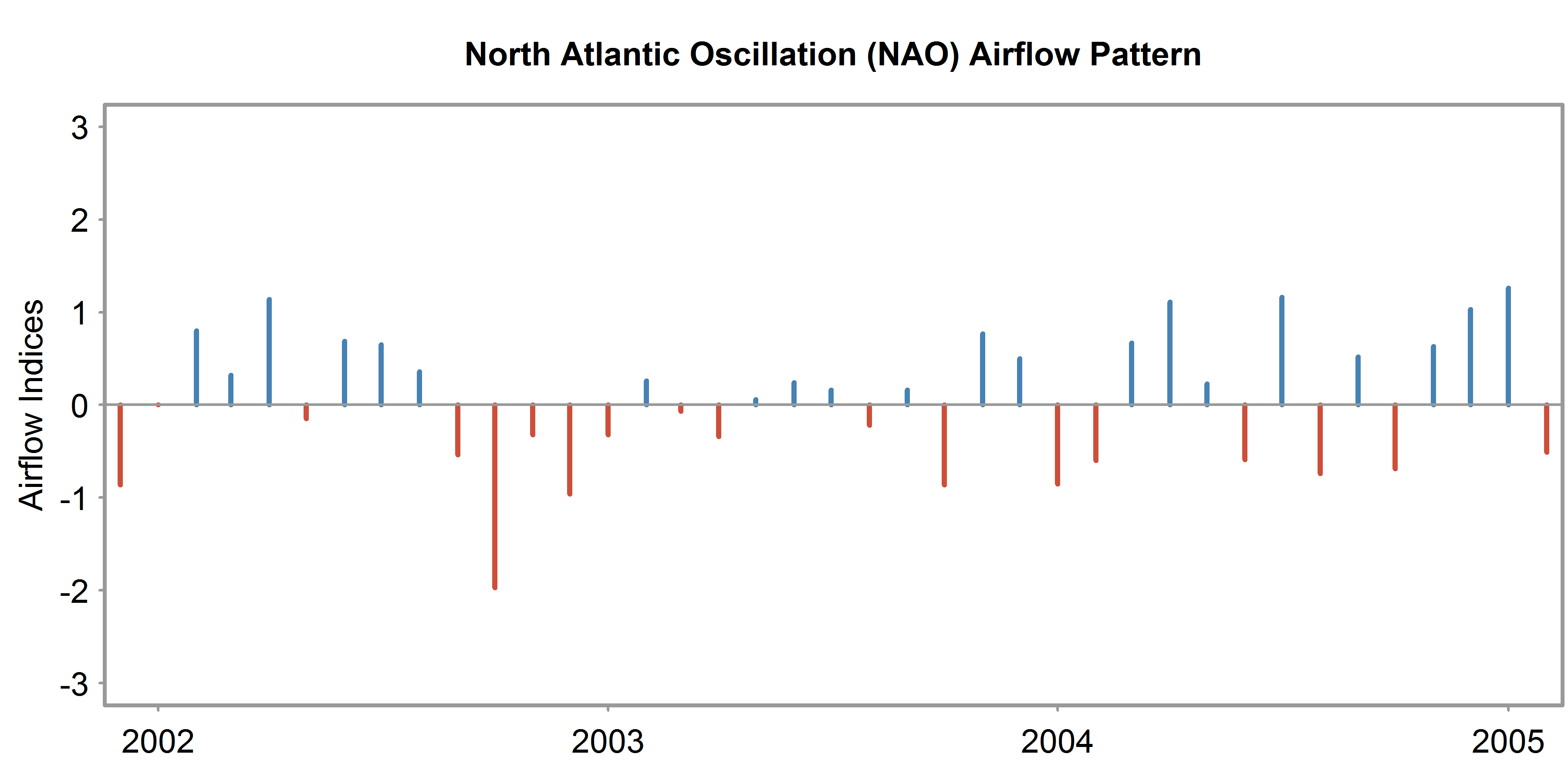

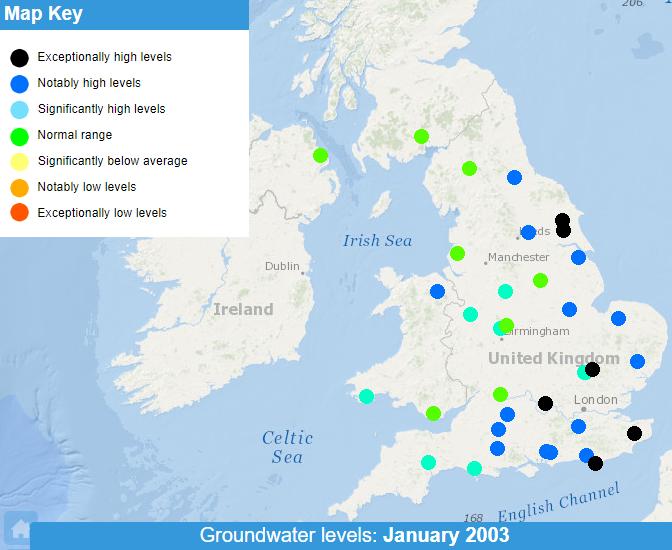

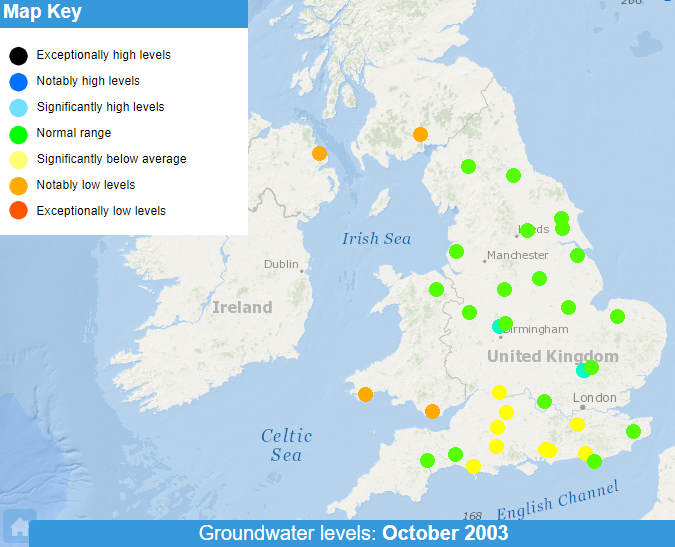

The extreme drought and heatwave that hit the United Kingdom and continental Europe during the summer of 2003 led to substantial social and environmental effects but, in relation to water resources stress, the UK’s general resilience to within-year rainfall deficiencies was well demonstrated.

Drought conditions became established over most of the UK during the late winter and early spring of 2002/2003. The spring period saw record-breaking lack of rainfall and gave way to long, warm summer. Exceptional evaporative demands contributed to the severe drought conditions through the summer and the associated environmental impacts assumed a greater political significance in the context of climate change projections.