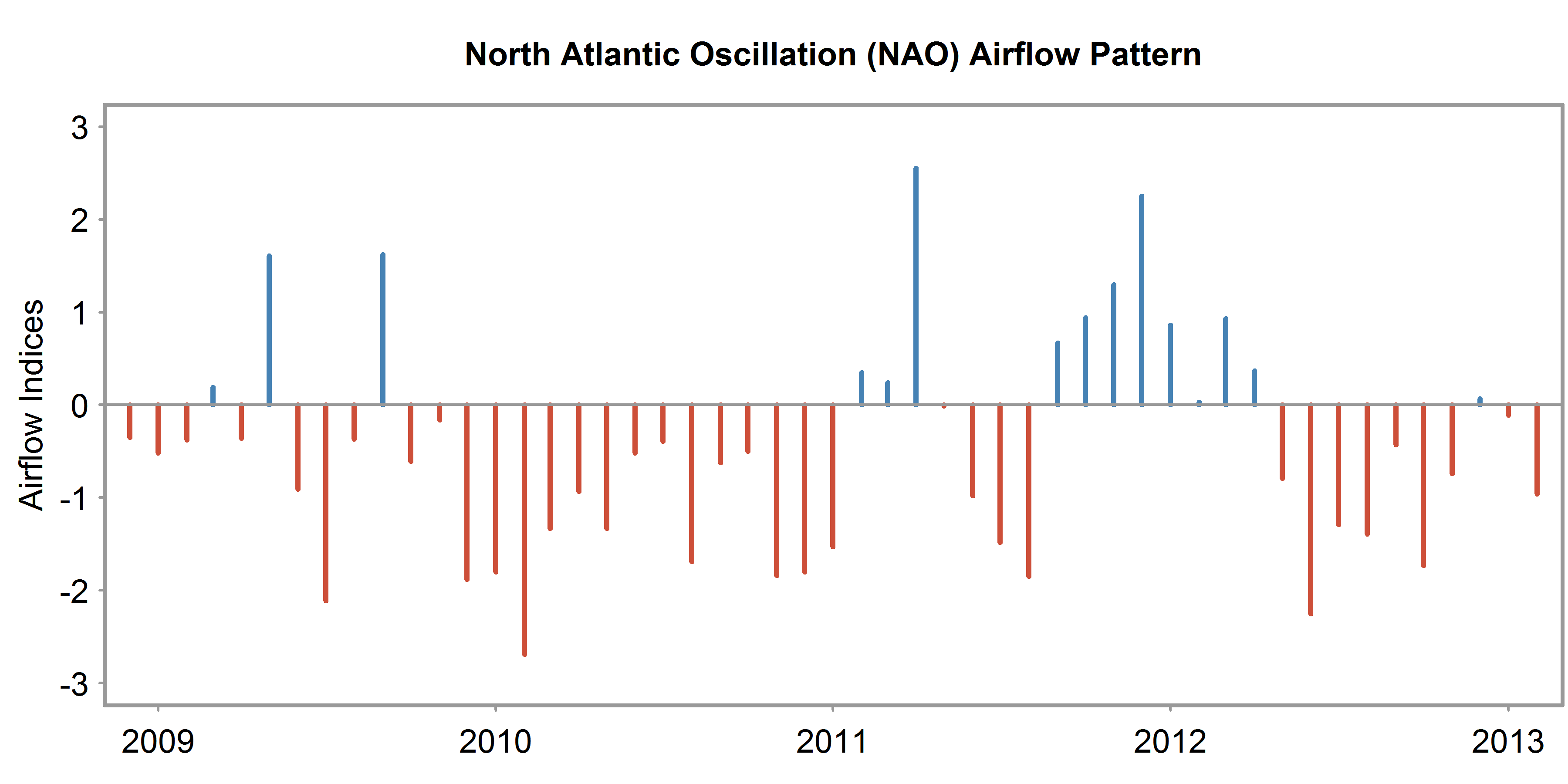

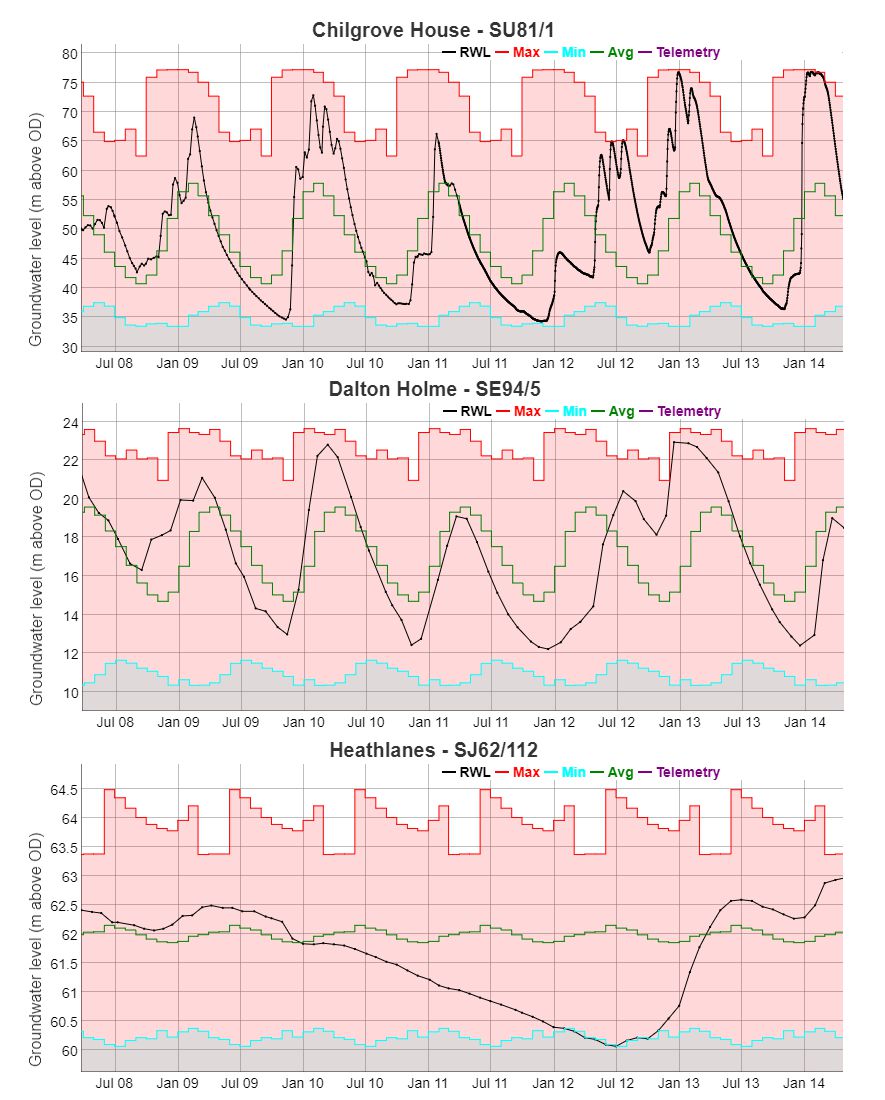

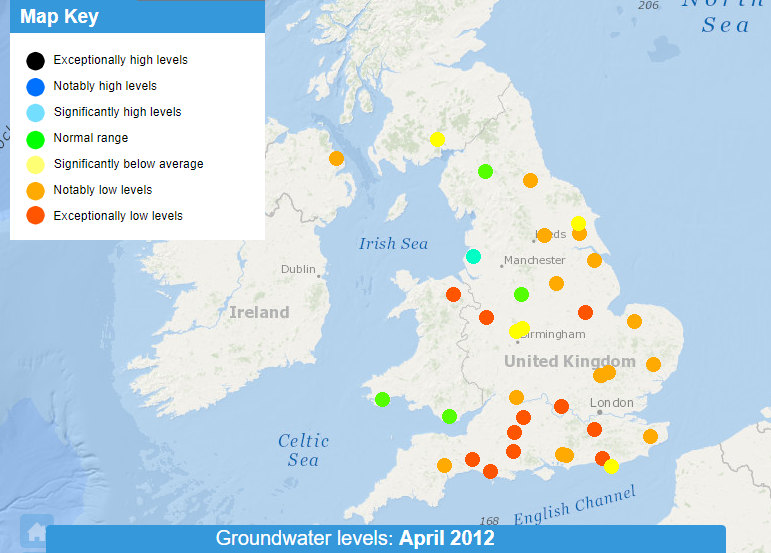

Across most of the UK, the 2010/2012 period was remarkable in climatic terms with exceptional departures from normal rainfall, runoff and aquifer recharge patterns. Generalising broadly, drought conditions developed through 2010, intensified during 2011 and were severe across much of England & Wales by the early spring of 2012. Record late spring and summer rainfall then triggered a hydrological transformation that has no close modern parallel. Seasonally extreme river flows were common through the summer, heralding further extensive flooding during the autumn and, particularly, the early winter when record runoff at the national scale provided a culmination to the wettest nine-month sequence for England & Wales in an instrumental record beginning in 1766.