Dr France Gerard (CEH) reports from the first field campaign conducted by the PARAGUAS research team in the high-altitude páramos of Boyacá, Colombia. PARAGUAS is investigating how people and plants are influencing water storage in páramos areas, which are the source of water for many in Colombia...

As I write, many of my PARAGUAS colleagues are with me in Boyacá, Colombia where we are halfway through our first field campaign, running from 15 February to 3 March 2019.

Our main objectives for this phase of the project are to:

- Define the boundaries of 12 ‘micro-cuencas’ (i.e. small watersheds) located across our study area, the páramo Guantiva-La Rusia.

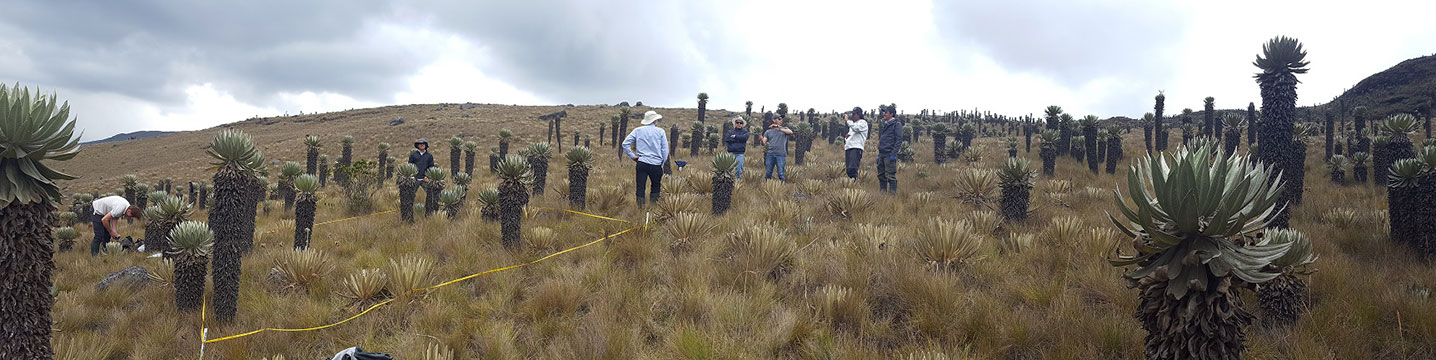

- Establish a number of survey plots (5m by 5m) across each of our micro-cuencas. These will help us characterise the different hydrological response classes that dominate each micro-cuenca in terms of soil characteristics, and the number and type of plants.

- Determine where to place a flow gauge and weather station. These installations will help us monitor the flow of water leaving the micro-cuenca and thus the water yield of the sites.

- Fly a drone over the survey plots and their surroundings to capture the spatial variation in hydrological response classes, help with the estimations of plant numbers and produce digital elevation models.

- Evaluate a preliminary radar (satellite) based map showing the spatial distribution in Guantiva-La Rusia of the peat-based wetlands, which form an integral and important part of the páramo. The water retention capacity of these wetlands is believed to play a major role in stabilising the water yield throughout the year.

With our páramo sites located at altitudes between 3500m and 4200m, a few of us, myself included, arrived three days early and stayed in Tunja (at 2810m), giving us the time to acclimatise. During our stay in Tunja we met with several of our Colombian collaborators at UPTC to visit the lab facilities they’ve made available to PARAGUAS, and discuss joint student projects.

We spent time working out how best to integrate a Colciencias-funded project led by Francisco Cortés Pérez (UPTC). This is investigating the effectiveness of introducing different types of fog catchers—ie, using naturally tall indigenous páramo plants or artificial screens—to increase the water yield of the páramo. During the earlier Colombia-Bio integration workshop held by NERC and AHRC in Bogotá, Francisco and I agreed that his study site, the páramo of Pan de Azúcar, should be one of the 12 PARAGUAS sites. The Pan de Azúcar is privately owned by Julián Barbosa (Fundación Tibairá) and managed as a nature reserve. Julián is passionate about conservation and is looking into ways in which he can sustainably use the páramo. In another páramo area, for example, he harvests honey and pollen from recently-introduced bee hives.

Espeletia health

We also took the opportunity to meet Amanda Varela Ramírez (Pontificia Universidad Javeriana) at the Chingaza National Park and collect drone imagery for plots where she is monitoring the health of Espeletia plants. This was possible thanks to the courtesy and support of the national park authorities who, at very short notice, gave us permission to fly our drone in the park. Espeletias are typically found in the páramos of Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, and are iconic plants due to their unique shape and beauty. Recently, however, Espeletia plants have started to die in large numbers and it is yet unclear why.

The long-term monitoring of the health of large quantities of individual plants will be key to help evaluate current hypotheses. In a small PARAGUAS spin-off project we plan to test if drone remote sensing could provide maps of individual living and dead plants.

Middle: Amanda explaining to Charles the hypotheses behind the death of the Espeletias that have been proposed.

Right: Amanda checking the health of an Espeletia plant.