A new Atlas of the Centipedes of Britain and Ireland is published today, the result of many years of work by both amateur and professional recorders in the Centipede Recording Scheme under the auspices of the British Myriapod and Isopod Group.

The atlas was compiled by A D (Tony) Barber with help from the Biological Records Centre at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. But, as Tony tells us,

“This atlas involved many people and local record centres contributing large numbers of records and specimens over many years and, in that sense, at least, they are the real authors.”

Tony has been interested in centipedes for many years and was co-author with Andy Keay of the 1988 Provisional Atlas of the Centipedes of the British Isles. He also published an AIDGAP key to the group in 2008 and a Linnean Society Synopsis in 2009. In 2021, he was given a Marsh Award for Entomology for his contributions to the study of these animals.

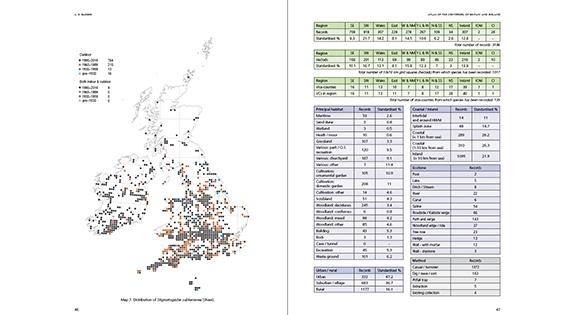

There are around 50 species of centipede reliably recorded in Britain, all of which are included in the new publication with hectad (10x10km square) distribution maps. From its inception, the Centipede Recording Scheme (and those for millipedes and woodlice) made an effort to collect habitat details in addition to recording presence, and this information is also presented within the Atlas, along with general and historical comments.

Centipedes are widespread and common and are easily found in both spring and autumn. They occur in all sorts of habitats including strongly human-influenced ones (from rubbish tips to royal gardens!), as well as very rural ones; and have even been found up to 1,000 metres on Snowdon.

Each species has its particular habitat preferences, and five of the species in the British Isles occur exclusively on the seashore. The most isolated location recorded is probably the uninhabited island of Boreray, six kilometres off St Kilda.

Indeed, their preference for specific habitats means centipedes are likely to be useful indicators of climate change and, as certain species are found in either urban or rural sites, they are good indicators of past and present human activity too.