Following the driest spring in England for 132 years, the Met Office forecasts for the coming months are uncertain. Hydrological ‘hindcasts’ exploring how weather conditions could have developed in past years mean scientists can be wiser before future events, explains Dr Wilson Chan, a hydroclimatologist at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

Following an exceptionally dry spring and rainfall deficits stretching over the past 12 months for some regions, river flows at the start of July were widely below normal, notably so across parts of central and eastern Britain.

In early June, Yorkshire was officially declared in drought, joining north-west England, which had already been in drought status since the end of May. By mid-July, the West and East Midlands were added to the list, while Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire, East Anglia, and the Thames region were designated as experiencing prolonged dry weather. Many other regions remain on alert as the situation continues to evolve.

In response, several water companies have introduced temporary use bans, the most recent being in Thames Water, across parts of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and Wiltshire, as well as areas served by Yorkshire Water, Southern Water, and South East Water. These measures – affecting a total of eight million people - reflect growing concern over water availability and the need to conserve resources.

Rainfall in June and July brought some relief to western and northeastern areas, helping to ease pressure on river flows. However, July has so far failed to deliver widespread recovery, with rainfall on course to be average or below average across many parts of the UK, especially southern England.

Prolonged drought conditions

Looking ahead, forecasts for the rest of summer and autumn remain uncertain; the Met Office three-month forecast suggests a roughly equal chance of either wet or dry conditions, with the Hydrological Outlook based on these forecasts showing higher likelihood of continued low river flows across eastern Britain.

What began earlier in the year as a ‘flash drought’ in northern and western areas has evolved. While recent rainfall has eased pressure in those regions, more drought-resilient areas are now experiencing more acute and prolonged drought conditions. This includes central and eastern England, buoyed by high groundwater levels following the wet winter, though these are now declining as they would usually over the summer.

Long-term planning several months or seasons ahead is vital for sectors like farming and water resources. Given uncertain forecasts, a common approach to assist planning is to ask what if a past dry year is repeated, like: ‘what if drought years like 1976 or 2022 are repeated again?’.

Answering this question relies on observations, and although the UK has relatively long records of observed river flows (with most starting in the 1960s and 70s), they are still limited when we want to consider rare outcomes as the full range of extremes is not well sampled.

The UNSEEN method

To anticipate more extreme but plausible outcomes, researchers have started using ‘hindcasts’ – thousands of simulated weather conditions (called an ‘ensemble’) that computer-based forecasting models consider may have happened at any given time in the past.

These hindcasts, from sources like the European Centre for Medium Range Forecasts (ECMWF), form a collection of ‘virtual observations’ many more times the number of actual observations. By using these hindcasts, climate extremes are much better sampled than in the observed record and can help shed light on possible unprecedented outcomes.

UKCEH scientists have applied this method – known as UNSEEN (Unprecedented simulated extremes using ensembles) – to explore how much worse the summer 2022 drought and the winter 2024 river flooding could have been. This helps us improve risk awareness of plausible worst cases for extreme events like floods and droughts.

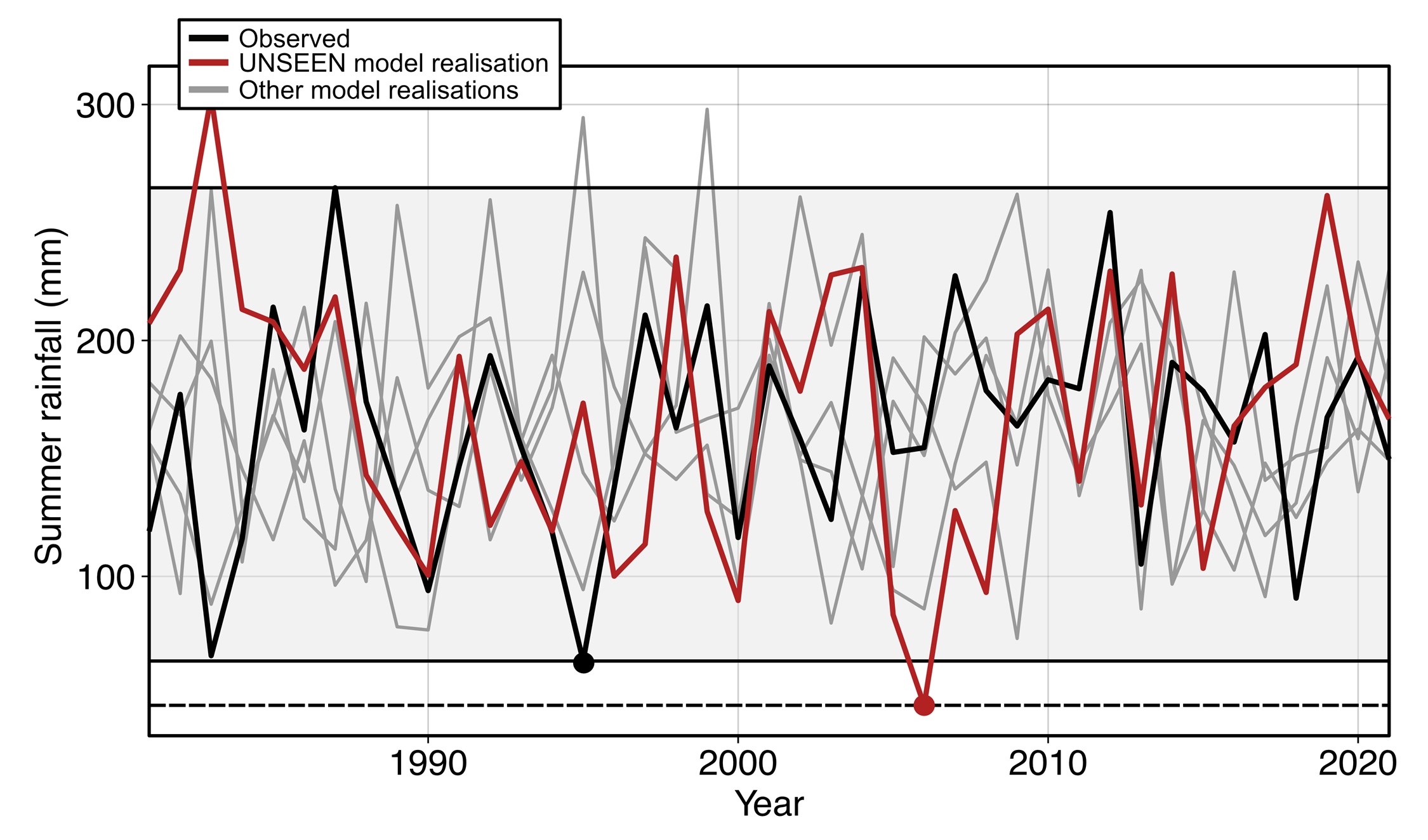

For example, the graph below shows observed summer rainfall since the 1980s averaged over East England (in black) and several simulated summer rainfall scenarios from the hindcast ensemble (in grey).

One of these scenarios from the hindcast ensemble, highlighted in red, shows a summer with even less rainfall than the driest observed summer in the hindcast period (ie 1995), while others contain months wetter than the wettest observed summer over this time period.

Preparing for the worst

Prolonged low rainfall in the UK is related to the position of the jet stream. If it is directed north of the UK, it will deflect rain-bearing systems from the Atlantic away from the UK and encourage high pressure conditions that bring dry, settled weather.

With over 3,000 plausible July-September simulated sequences in the hindcast archive, we can assess how river flows might change in response to different jet stream behaviour and associated rainfall patterns, including rare but plausible extremes.

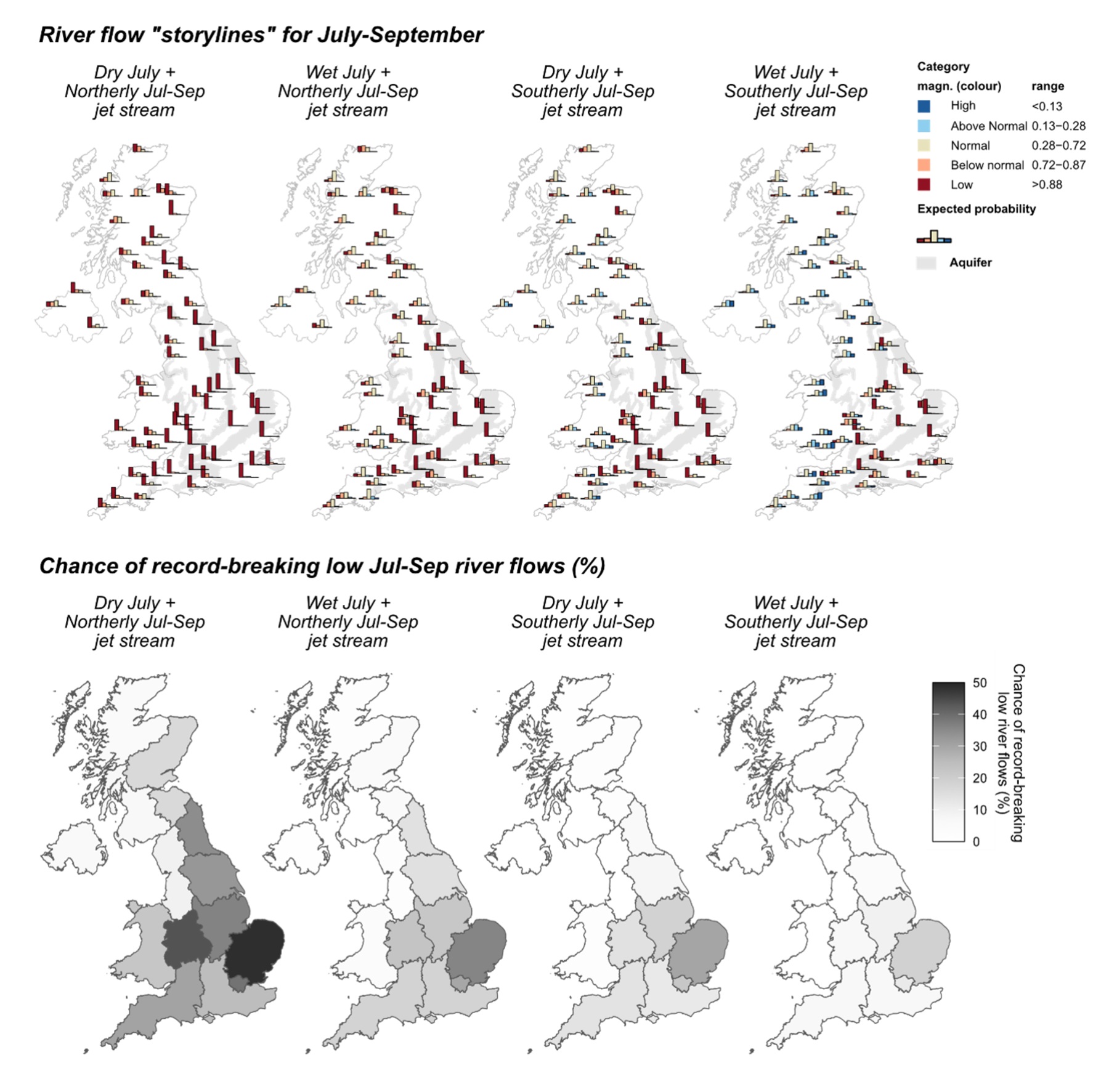

River flow simulations starting from current conditions initialised with observed data until the end of June 2025, followed by the thousands of possible July-September sequences from the hindcast archive, show a wide range of possible river flow outcomes by September. This large set of possibilities are grouped into four ‘what-if’ storylines.

In the worst-case scenario, where a drier-than-average July is combined with sustained high pressure conditions over July-September due to a shifted jet stream positioned to the north of the UK, river flows could be in the Low category across the country by September. In this case, the probability of catchments breaking their lowest July-September river flows on record is heightened, especially across central and eastern Britain.

If July turns out to be wetter than average, the same stationary high pressure conditions across July-September would have a less severe impacts (ie the second storyline), as some catchments – like those in eastern Scotland – could recover relatively rapidly from sufficient July rainfall.

Conversely, if the jet stream over July-September stays towards the south of the UK, the rainy and unsettled low pressure conditions that it brings could ease the risk of drought, and the chance of record-breaking low river flows is mostly eradicated. However, even then, parts of central and southeast England could still be at risk of experiencing very low flows, with some chance of record-breaking low flows by September remaining.

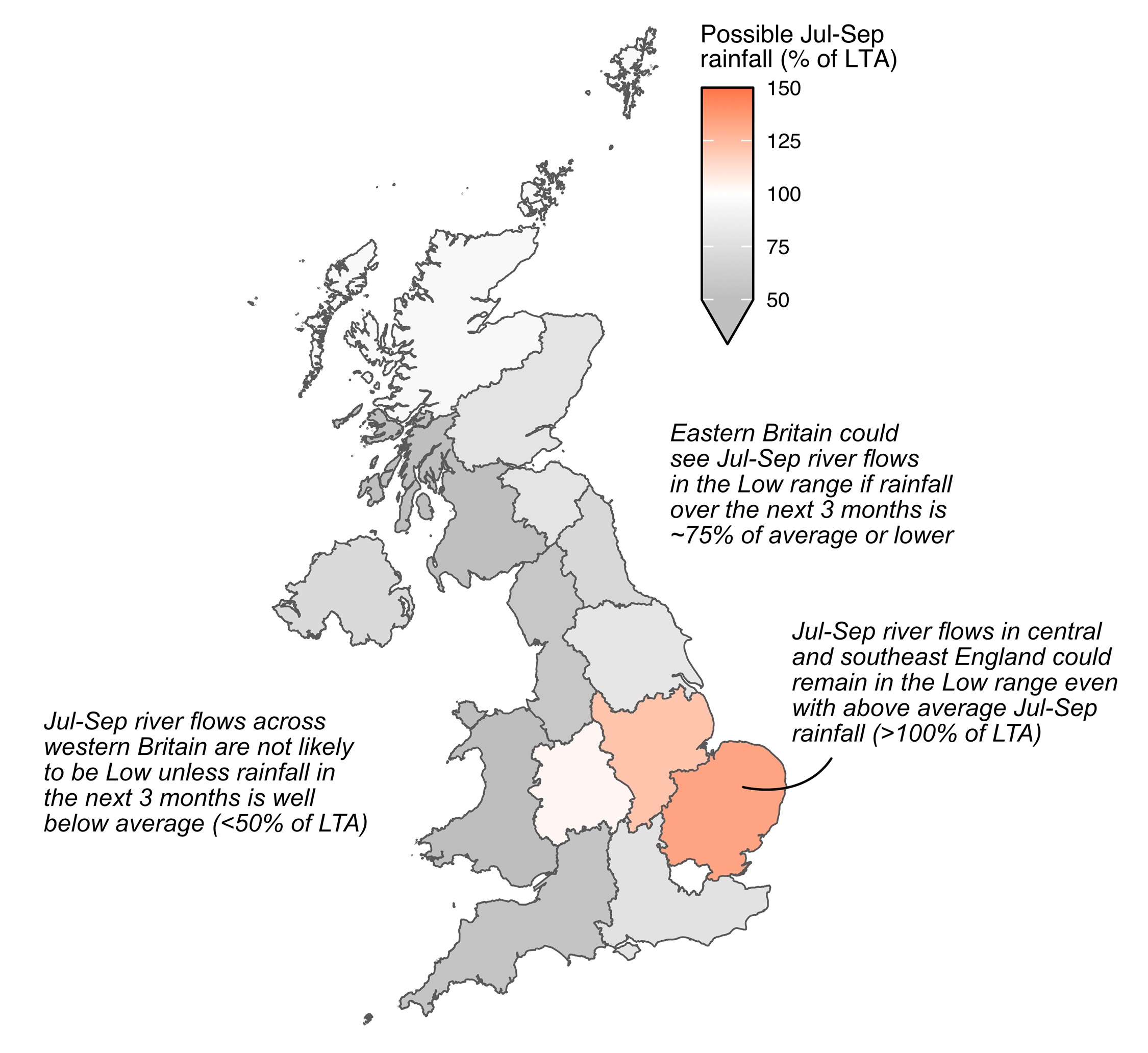

Looking across the thousands of possible July-September scenarios, even with above average rainfall over the next three months, river flows across central and southeast England is likely to remain in the Low category, echoing analysis in the latest Hydrological Outlook. Significantly above-average rainfall is required, over many months, to return to normal conditions.

In northeast England and east Scotland, river flows are also likely to remain low if these regions receive three-quarters of average July-September rainfall or less. A short-term recovery is considered unlikely without sustained, exceptional rainfall.

In contrast, rainfall over recent months across western Britain has buffered river flows, so they are less likely to fall into the Low category, unless rainfall over the next three months is significantly below average (ie 50% of average or less).

Continuous monitoring of the current drought and the trajectories of river flows and soil moisture conditions through the rest of July and early autumn will be essential. Forecasts of weather patterns of the summer and autumn months may give us a sign of which ‘storyline’ we might end up following.

The UNSEEN method offers a novel opportunity to exploring ‘what-if’ storylines by making use of the large sample of physically plausible weather sequences simulated by dynamical weather models. This helps fill the gaps of our limited observations to help plan ahead and anticipate plausible worst cases, and to explore the relative roles of different atmospheric circulation mechanisms on river flows.

With contributions from Lucy Barker, Steve Turner and Jamie Hannaford.

Further information

Read the latest Hydrological Outlook

Monitor the current conditions using the UK Water Resources Portal